Once the team is ready to begin the work, a solid understanding of the context is required. This step involves characterising the stakeholders, the socioeconomic and biophysical situation, current threats to ecosystems, and issues to be addressed. Its expected outputs are:

- A stakeholder analysis and a stakeholder engagement strategy

- Initial contact with stakeholders

- A comprehensive understanding of the local context.

Task 2 A. Stakeholder analysis and stakeholder engagement strategy

What this task is about

Once you are organised, one of the first tasks is to identify who the key stakeholders are in relation to the issue or challenge being addressed. You will then need to contact them and plan how to engage them in subsequent steps of the process. Relevant stakeholders typically include individuals, groups and organisations within the territory who make decisions about it or influence its status, and/or who are impacted by (or indeed impact upon) the challenge or issue being addressed. Examples are:

- Conservation authorities (e.g. national park department, watershed management)

- Local government authorities (e.g. at district level) and local or regional representatives of national authorities (e.g. the environment ministry).

- Representatives of villages or communities, including indigenous groups

- Representatives of important economic sectors with an interest in or an influence on the territory (agriculture, tourism, industry, etc.)

- Locally active NGOs or conservation groups

- Local universities or research centres

- Other important interest groups with a relation to the territory or issues at stake

It is crucial to understand the stakeholders’ current attitude to conservation, so it will be necessary to consider their interests, issues and concerns, including local culture. It is also useful to understand relationships between the different stakeholders. Understanding conflicts is particularly important. Reducing conflicts can be an objective in itself, but existing conflicts need to be taken into account during the engagement process. For instance, be careful if you invite conflicting parties to a joint workshop, since it may hinder constructive discussion and progress. On the other hand, you should also be aware of existing cooperation and collaboration, where people are already organised or working together. Such collaboration can be crucial to a successful process and to the design and implementation of policy and financing instruments.

![]() Be aware of – and avoid – conflicts! Please click to learn morePre-existing conflicts play a subtle but important role in Thailand that is difficult for outsiders to comprehend. For instance, there is a traditional political divide between ‘red shirt’ and ‘yellow shirt’ parties. If an important supporter of the project is known to be on one side, stakeholders on the other may keep their distance. ECO-BEST’s strategy was to focus all debates strictly on improving the common good and on specific ecological issues, and to avoid any political debate.

Be aware of – and avoid – conflicts! Please click to learn morePre-existing conflicts play a subtle but important role in Thailand that is difficult for outsiders to comprehend. For instance, there is a traditional political divide between ‘red shirt’ and ‘yellow shirt’ parties. If an important supporter of the project is known to be on one side, stakeholders on the other may keep their distance. ECO-BEST’s strategy was to focus all debates strictly on improving the common good and on specific ecological issues, and to avoid any political debate.

A stakeholder-inclusive process has many merits, but you need to take into account the local situation, conflictive relationships and also limits to resources, etc. Therefore, it is crucial to consider whether to involve a particular stakeholder or not – and if so, why and when.

How to go about Task 2 A

With your team, particularly its members with local knowledge, first make a list of all relevant stake-holders. The Stakeholder Mapping Table in Template 2A proposes one way of summarising and documenting the most important aspects of the stakeholder analysis. Feel free to add columns to the table if you can think of important additional aspects. You may also prefer another form of visualization.

![]() There are many tools for summarising and visualising stakeholder information! Please click to learn moreExample from Palau – comes soon.

There are many tools for summarising and visualising stakeholder information! Please click to learn moreExample from Palau – comes soon.

![]() A role-play simulation of a stakeholder discussion can be instructive! Please click to learn moreWhen you plan a stakeholder workshop, it can be an instructive exercise to simulate stakeholder discussions in a role-play fashion within your team. Allocate the roles of key stakeholders and the role of facilitator or moderator, and do a trial with the questions or exercises you have in mind. A lot can be learned from this simulation. How would different stakeholders react? What are the challenges to communicate concepts or issues? Could conflicts arise and how can they be avoided or dealt with? Would facilitation by a “neutral” outsider or a professional facilitator be an advantage?

A role-play simulation of a stakeholder discussion can be instructive! Please click to learn moreWhen you plan a stakeholder workshop, it can be an instructive exercise to simulate stakeholder discussions in a role-play fashion within your team. Allocate the roles of key stakeholders and the role of facilitator or moderator, and do a trial with the questions or exercises you have in mind. A lot can be learned from this simulation. How would different stakeholders react? What are the challenges to communicate concepts or issues? Could conflicts arise and how can they be avoided or dealt with? Would facilitation by a “neutral” outsider or a professional facilitator be an advantage?

As described above, consider carefully how to contact and engage the stakeholders appropriately. It may not be a good idea simply to invite them all to the first workshop and expect high attendance and general interest. Rather, stakeholders should be targeted individually, using existing local networks and taking account of local customs. For local decision makers and opinion leaders in particular (e.g. village heads) it might make sense to introduce the study and generate their interest and support before such a workshop. Personal meetings or small group meetings could be used to distribute concise information in the local language. This could help stakeholders to understand the study, which they could then disseminate to their local networks. You could also present the information during workshops organised by others. Reflection and discussion within the team will help to find the best approach.

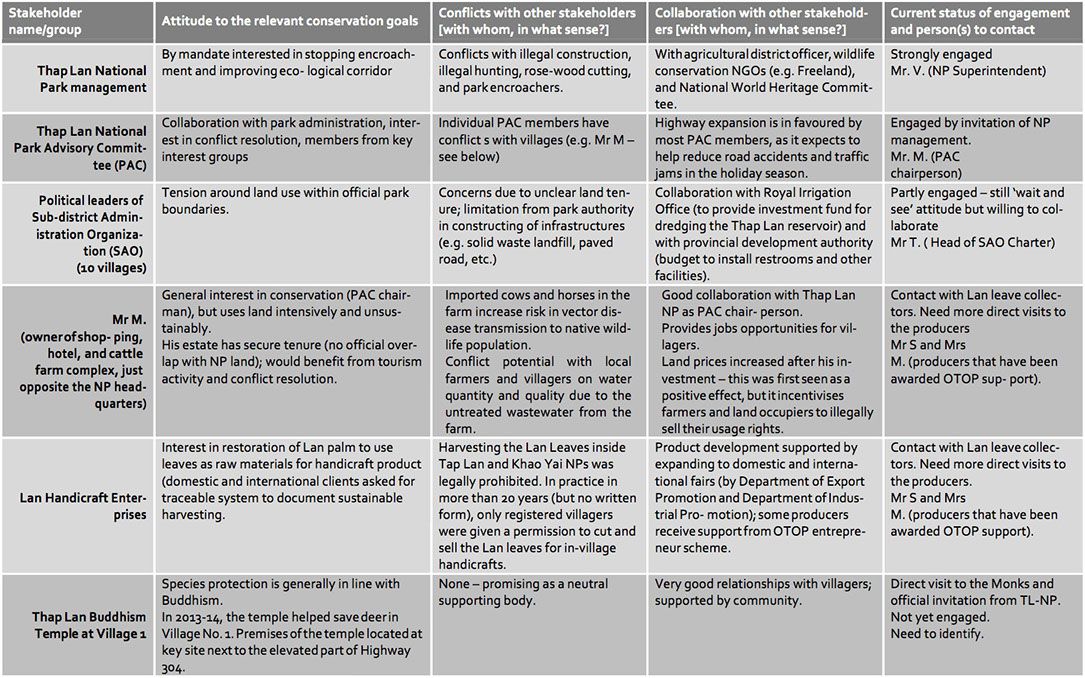

![]() Template 2A: Stakeholder Mapping Table (Examples from Bu Phram, Thailand) Download: empty filled out Please click to learn more

Template 2A: Stakeholder Mapping Table (Examples from Bu Phram, Thailand) Download: empty filled out Please click to learn more

Task 2 B. Scoping the environmental situation

What this task is about

A solid understanding of the local context is crucial for making appropriate analyses and choices. The broad goal of environmental scoping is to describe the current status of the natural environment in the study site, to provide a general background to where the work is taking place. Scoping also serves to investigate or flag particular topics, conditions or concerns which relate specifically to the objectives and issues being addressed. You need to give careful thought to align the focus and boundaries of the environmental scoping with the specific management issues. While it is useful to paint a broad picture in order to set the scene, scoping exercises sometimes try to cover too much detail. To include every aspect of the land, resources, biodiversity and biophysical conditions is rarely necessary or useful. Of primary interest are the environmental endowments and conditions which affect peoples’ livelihoods and economic opportunities, and which are affected by them. In addition, already existing plans, measures and policies for conservation should be understood.

![]() Use the momentum of existing policies and windows of opportunity! Please click to learn moreIn Bu Phram (Thailand), the goal was to improve the ecological conditions of a corridor between two national parks, in order to maintain the UNESCO WHS status of ‘outstanding universal value’. National plans and high-level political support for improving the wildlife corridor helped to generate momentum for the ECO-BEST project.

Use the momentum of existing policies and windows of opportunity! Please click to learn moreIn Bu Phram (Thailand), the goal was to improve the ecological conditions of a corridor between two national parks, in order to maintain the UNESCO WHS status of ‘outstanding universal value’. National plans and high-level political support for improving the wildlife corridor helped to generate momentum for the ECO-BEST project.

How to go about Task 2 B

It is sensible for the team to compile a checklist of exactly what information to collect in the environmental scoping, and decide who will gather it and how. The checklist in Template 2 B/C raises questions to address. Environmental or biophysical experts on the team will be mainly responsible for undertaking the environmental scoping, but they should seek input from other members. There are various ways to collect data. Where time, money and staff capacity are limited, it may be done as a desk review or based only on secondary sources (for example through literature review, compilation of existing GIS data and/or expert consultation). In most cases, however, it should also be possible to conduct a brief field study. Unless the area is very large, or the issues being addressed are highly complex, two to three days would usually be sufficient for this. As well as observation, rapid surveys and mapping, collation of statistics and other methods of data collection, dialogue should be initiated with key stakeholders and experts on site. Face-to-face meetings not only provide data on the topics listed above but are an effective way to inform stakeholders about the scoping exercise, and to encourage their buy-in to the process and their input.

It is also important to coordinate the environmental scoping closely with the socio-economic scoping described below in Task 2C. Ideally, perform them simultaneously.

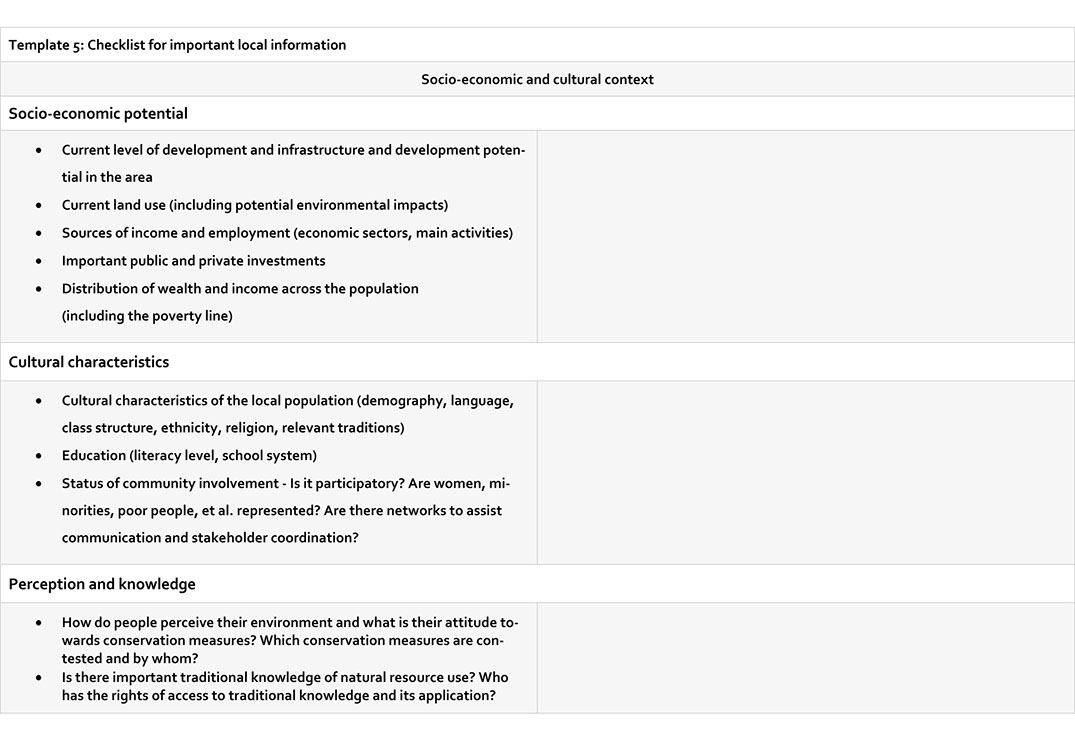

![]() Template 2B & 2C: Checklist for important local information (env. context) Download: Checklist Please click to learn more

Template 2B & 2C: Checklist for important local information (env. context) Download: Checklist Please click to learn more

Task 2 C. Understanding institutions, laws, policies, economic and social conditions

What this task is about

It is important to gather information on the social, economic, political, legal and cultural conditions of the area early on – but don’t spend too much time collecting all possible data and making over-complex analyses. The key challenge is to filter and target the information in response to specific needs. Much of the information will be readily available, for instance from previous projects or initiatives in the area.

It is important to understand that policies made at national and provincial level affect conservation and livelihood outcomes at local level. Your project or initiative may impact on these policies but in most cases you cannot count on changing them. Higher level policies are an important part of the regulatory framework within which you have to operate.

It is also very important to consider competition with current or future income-generating interventions that require local people’s attention, time and effort.

![]() Understand complementary and competing programmes! Please click to learn moreIn Pang-Mao (Thailand), a government rural development programme had allocated several million Baht for both research and development of agriculture activities that directly benefit farming families. For farmers, income from ecosystem services opportunities would very likely be a minor additional benefit within a heavily subsidised policy on agriculture extension and conventional environment activities.

Understand complementary and competing programmes! Please click to learn moreIn Pang-Mao (Thailand), a government rural development programme had allocated several million Baht for both research and development of agriculture activities that directly benefit farming families. For farmers, income from ecosystem services opportunities would very likely be a minor additional benefit within a heavily subsidised policy on agriculture extension and conventional environment activities.

How to go about Task 2 C

The process here is similar to Task 2B, and information for both steps can be gathered in parallel. The two last parts of Template 2 B/C present checklists with questions to be addressed for compiling and structuring an important local information sheet. Of course, this database is flexible and can be updated when new or more specific information arises: for instance, during stakeholder workshops or expert consultations. Note that the sub-questions and bullet points in the different sections are meant to provide guidance, but not all need to be answered separately. If it seems useful to contract external consult-ants to analyse the local context, then the checklist can serve as guidance in formulating terms of reference (ToRs).

![]() A document with the context information can also serve to inform others! Please click to learn moreThe document on local information can also be useful in sharing relevant information with others, such as new team members or experts, and is a quick and efficient way of helping them to gain a comprehensive understanding of the context.

A document with the context information can also serve to inform others! Please click to learn moreThe document on local information can also be useful in sharing relevant information with others, such as new team members or experts, and is a quick and efficient way of helping them to gain a comprehensive understanding of the context.

![]() Template 2B & 2C: Checklist for important local information Download: Checklist Please click to learn more

Template 2B & 2C: Checklist for important local information Download: Checklist Please click to learn more

Selected references and further guidance for Step 2

The Community Tool Box (2014) provides comprehensive information for identifying and analysing stakeholders and their interests (Task 2A).

The Frogleaps (2013) tool “Understanding your target audiences” can help better understand stakeholders’ behaviour, knowledge, beliefs and attitudes (Task 2A).

Chapter 2 of the ‘Handbook on Planning, Monitoring and Evaluating for Development’ (UNDP, 2009) helps to plan effective and active stakeholder engagement and provides useful methods (Task 2A).

The guideline ‘Stakeholder collaboration – Building bridges for conservation’ by WWF (2000) explains the principles of stakeholder collaboration for conservation, introduces a range of tools, and reports on case studies (Task 2A).

The handbook on ‘Participatory Rural Appraisal for Community Forest Management. Tools and Techniques’ by the Asia Forest Network (2002) offers an overview of methods and tools to engage stakeholders and develop a joint understanding of the relevant issues around natural resources use (Task 2B & 2C)

Imprint

Introduction

Step 1:

Getting

organized

Step 3:

Identifying

ecosystem service opportunities

Step 2:

Scoping the

context &

stakeholders

Step 4:

Selecting

policy

instruments

Step 6:

Designing

and agreeing

on the instrument

Step 5:

Sketching

out the

instrument

Step 7:

Planning

for

implementation

Datenschutz

Resources

EN

ES